Featured Member: Mara Josi

Featured Member shines a spotlight on the diverse research interests of, and the exciting projects undertaken by, those affiliated with the Cultural Memory Studies Initiative. In this sixteenth instalment of the series, we speak to Mara Josi, a postdoctoral researcher working on Italian Holocaust literature. Dr Josi obtained her PhD from University of Cambridge and, before joining Ghent University, worked at University College Dublin and the University of Manchester. In this interview, she talks about her journey in memory studies, her past and future work on Italian culture, the important role that literature plays in memory, and the significance of collaboration in today’s academic world.

Can you tell us a little about your academic path? How did you develop an interest in memory studies?

My interest in memory studies began almost ten years ago, during my BA and MA at the University of Turin. It really took off when I started my PhD at the University of Cambridge, where I focused on Italian Holocaust literature, specifically looking at how a particular event from World War II has been remembered through literary texts. I was particularly interested in how literature has shaped the cultural and collective memory of the largest round-up in Italy during the Nazi occupation. I later developed my PhD dissertation into my first monograph during my time as an IRC Postdoctoral Fellow at University College Dublin and further refined it while I was a lecturer at the University of Manchester. The book was very well received and was recently awarded the Premio Internazionale Ennio Flaiano d’Italianistica. Within less than a year, book launches were held in Oxford, Dublin, Rome, and Genoa. I was invited to produce a podcast by NewBooksNetwork and interviewed for a national broadcast. This attention reflects the growing interest in the field of memory studies on both an academic and non-academic level. I think people are eager to explore how memory functions both personally and collectively, driven by a desire to understand how literature influences our thinking and inspires behavioural change.

Last year, I joined Ghent University on an FWO Junior Fellowship. At UGent, I found an incredibly vibrant and supportive academic environment, especially in the field of memory studies. Here, I’ve been working on my current project, which introduces a new category of Holocaust-related literature: texts written by Italian Jews who escaped deportation and narrated their experiences in hiding. My research explores how these works can reshape our understanding of the period of discrimination and persecution in Italy.

My academic journey in memory studies has been profoundly shaped by the scholars who’ve guided me along the way. Their support has deeply influenced not only my work but also my personal growth as a researcher. I’m truly grateful for the people I’ve met along the way.

You have worked extensively on the Italian memory of the Holocaust. Can you tell us something about the development of this strain of memory in Italian culture?

The way Italy has remembered and written about the Holocaust has changed over time, reflecting different phases in the country’s history. Right after World War II, there was little interest in the Holocaust, and the voices of Jewish survivors were largely ignored. The trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961 was a turning point, which brought greater attention to extermination and concentration camps. And yet, the Holocaust was still often seen as something for which only the Nazis were responsible. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Italians began to confront their role in the persecution of Jews, leading to efforts to challenge and move beyond the myth of good Italian people and that of the Resistance. A growing awareness of Italian complicity in the discrimination, persecution, and deportation of Italian Jews emerged, thanks to the work of historians, the publication of testimonial writings, and the tireless efforts of survivors speaking in schools to educate younger generations.

In recent years, Holocaust remembrance in Italy has become even more significant, especially with the rise of nationalist parties and increasing numbers of anti-Semitic incidents. Public debate has intensified, particularly around figures like Liliana Segre, a Holocaust survivor and Senator for Life, who has faced numerous direct anti-Semitic threats. These discussions have been further complicated by current events, such as the escalation of the Israeli-Hamas conflict, which has led to alarming distortions of the meaning and memory of the Holocaust, as well as the recollection of its victims, survivors, helpers, perpetrators, implicated subjects, and bystanders for political goals.

Your monograph deals with the cultural memory of 16 October 1943, the most tragic round-up of Jewish citizens in Italy. Can you talk about this event and its memory in Italian literature?

The Roman round-up is notable in its own right and in relation to the deportations that occurred elsewhere in Italy and in Europe. It took place after Rome had been declared an ‘open city’ in August 1943, in what was then the southernmost city in the Italian Social Republic (RSI) after the Allies had reached Naples in late September. It was perpetrated in the heart of the Roman Catholic world, in a city of international as well as national significance.

In 1943 one of the most populous Italian Jewish communities was based in Rome. On Saturday 16 October 1943, 1259 people were arrested by the Nazi occupiers and gathered in a temporary detention centre for two days. On 17 October, 252 of 1259 were freed because they had been recognised as what the Nazis defined as ‘non-Jews’. The rest were deported on 18 October from a local railway station to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where they arrived in the night of Friday 22 October. Only sixteen people survived and returned to Rome after the end of the World War II.

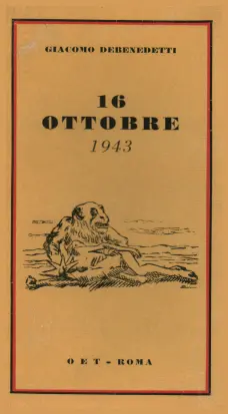

In the last eighty years, almost twenty books have been published that prompt, albeit sometimes only indirectly, reflections on the Roman round-up and give us a sense of the spread of the literary re-elaboration of the event throughout the decades. They describe, in more or less detail, how the dehumanisation process began, how Jews were taken from their houses, how they were herded, how they were put onto cattle-trucks, and how they were deported to Auschwitz. In my book, I explore four texts which I showed to be especially influential in both personal and collective terms, by merging affect theory and cultural memory studies. My analysis starts with Giacomo Debenedetti’s 16 ottobre 1943, first published in 1944 in a journal and then in 1945 as a book. This was the earliest attempt at re-elaborating and capturing in narrative form the Roman round-up. 16 ottobre started a process of integrating the persecution of the Jews in Italy into the national narrative and national literature. It became a point of reference for all the literary works which followed.

In your current research you conceptualise the literature of hiding as a new category within Italian Holocaust literature. Can you tell us a little more about this?

While conducting my research on 16 October 1943, I encountered texts by Jewish authors who evaded arrests and deportation by going into hiding. From that moment onwards, I kept digging, and I expanded my area of enquiry from Rome to the Italian peninsula.

There are a growing number of studies devoted to historical accounts of European Jews who escaped the Holocaust by living out of sight or under false documents. But at the moment, no study has provided a systematic consideration or comprehensive analysis of the literary texts reporting on the experience of hiding. This is what I am doing, starting from the Italian context, which is particularly interesting and constructive for such an enquiry because Italy counts the highest percentage (81%) of Jews who survived by going into hiding during the Nazi occupation of Europe.

By working on texts published from 1945 up to the present day, I have now built up a corpus of approximately 35 texts of different genres which report on life in hiding in occupied Italy. From the analysis of this corpus, I set up what I call “the literature of hiding”, a new category of Holocaust-related literature through which I further develop the field of Holocaust studies by blurring the boundaries of Holocaust literature and blurring the physiognomy of what has been regarded so far as a Holocaust survivor. In other words, my research activity considers what Holocaust testimonial literature signifies outside the universe of concentration and extermination camps, identifies and inventories the characteristics of “the literature of hiding”, and examines the extent to which this literature can reshape how the period of discrimination and persecution in Italy (1938-1945) has been publicly remembered so far. It helps advance the scholarly debate about the experiences of Italian Jews, the role of Italian perpetrators, collaborators, implicated subjects, and bystanders, as well as the position of Italian helpers in 1938-1945 Italy.

Are there any specific texts, concepts, or methods from memory studies that you have found particularly useful in your work?

I have always found the dynamic interplay between history, memory, and literature intriguing. This idea of a triangular relationship between history, memory, and literature has its roots in the first decades of the twentieth century, specifically in Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre’s theories of history. According to Bloch and Febvre, the past can be traced in documents which have not traditionally been assumed to transmit historical data, providing different but also foundational insights into the past through collective representations, myths, and images. Literary texts can take facts, stories, and experiences which had been neglected, dismissed, overlooked, forgotten, or ignored and transform them into something that is memorable. Especially after the impact of the Holocaust, literature has become an authoritative medium for the transmission of memory and the representation of that past.

What I do is explore how literature plays a role in shaping individual and collective memory, influencing both readers and society. Such analysis fosters our understanding of the factors influencing human thought, processes change, and prompts reflection on questions such as “Why and how do we remember? Why do we forget? And why and how do we omit?”

The theoretical framework I set up merges notions of cultural memory studies with affect theory. This framework is mostly indebted to Astrid Erll’s modes of writing the past, Ann Rigney’s five types of interaction between literature and cultural memory, Alison Landsberg’s prosthetic memory, and theories of emotions applied to literature by Terence Cave and by Caroline Pirlet and Andreas Wirag, for example.

Your work on memory has mainly focused on literature. What are the challenges? Why is literature important for issues of memory?

My biggest challenge is related to the processes of tracing similarities and differences among the texts I have been working on to try to understand how literature can have an impact on the individual and society. Despite the differences in genre, personal experience, and combination of historical sources and personal memories, the authors I worked on share recurrent themes in their treatment of discrimination and persecution in Italy and develop similar literary strategies and techniques. They combine historical facts and personal stories in narrative forms which transmit the past in and through lived experience. They use a range of techniques such as elaborate first-person narratives, detailed descriptions of everyday life, and present-tense voice to convey embodied and seemingly immediate experiences. They address readers in intimate ways, typical of direct, personal, and informal communication. These and other strategies involve readers in their stories and create collective affective bonds within and across generations. In this sense, by combining notions of cultural memory studies and affect theory, I show how these texts reactivate and re-embody distant individual and social memories, represent them in familiar forms of mediation and aesthetic expression, and create a sense of shared social space and historical time in readers, thus facilitating their understanding and recollection of the period of discrimination and persecution in Italy.

Are there any recent or forthcoming conferences, exhibitions, or other events that you are particularly enthusiastic about?

In 2023, the eightieth anniversary of the Roman round-up was commemorated with a range of public events aimed at highlighting the dangers of discrimination and persecution.

There were theatre performances, film screenings, readings, talks, conferences, and even guided walks through key deportation sites. Autumn 2023 was especially stimulating for me, as it coincided with the release of my book on the cultural memory of 16 October 1943. I was lucky enough to be invited to one of these events, where I presented my book in conversation with two historians. The event also featured semi-staged readings of the four texts I analysed, accompanied by piano solos between each reading. It was an incredibly moving experience, especially with survivors in the audience — people who, as children, narrowly escaped arrest and deportation. Their presence brought an emotional weight to the occasion that I’ll never forget.

Looking ahead, I’m really excited about the Mnemonics Summer School in 2025, which will be held at UGent. The theme, “Memory and Responsibility,” couldn’t resonate more with my research. I’m currently working on a chapter which focuses on how literature shapes societal understanding of hidden forms of discrimination and persecution, and how it can drive people to take action, so I’m particularly eager to see where young researchers are focusing their attention. It promises to be an inspiring event!

You have recently been appointed as an Assistant Professor in Italian Studies at University College Dublin. Congratulations! What were the most important experiences you had as a postdoctoral researcher that helped you get this job?

Thank you! I’m really excited to begin in this new role, but at the same time I’m genuinely sorry to leave UGent, where I’ve had the chance to work with such incredibly knowledgeable and generous scholars. Regarding your question, every step, project, and research environment in my academic path mattered, and to be awarded a prestigious FWO fellowship was surely an important element in this process. But more than to a specific experience, I would like to refer to an aspect of each of the experiences I have had since my PhD: collaboration between people. I believe it has been key to my growth as an academic and has significantly shaped my multidisciplinary approach to Italian culture and memory. Since my PhD days, I’ve joined various research centres and institutes tied to the universities I was part of: the Centre for War Studies at UCD, the Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Manchester, and the Cultural Memory Studies Initiative at UGent, for example. Through them, I’ve met colleagues who, sometimes without even knowing it, helped push my thinking forward. In the same spirit, last year at UGent, I joined the coordination of the Literary Studies Workshop, which provides a safe, stimulating space where senior scholars give feedback to junior researchers, helping them refine articles to be published, applications to be submitted, and research projects to be honed. I feel these events are constructive for both junior and senior participants, as they involve discussing cutting-edge research projects and ideas with intellectual rigour and generosity. So I think that probably collaboration is the answer to your question. It is particularly important in our field, where academic work is often considered to be solitary. I truly think that spending time together — whether in shared offices, feedback sessions, research events, or even just over a cup of coffee — makes a huge difference in how we approach our personal development as researchers, our ideas, and any new work environment.

Interview conducted via email by Guido Bartolini and Stef Craps.