Featured Member: Tine Vekemans

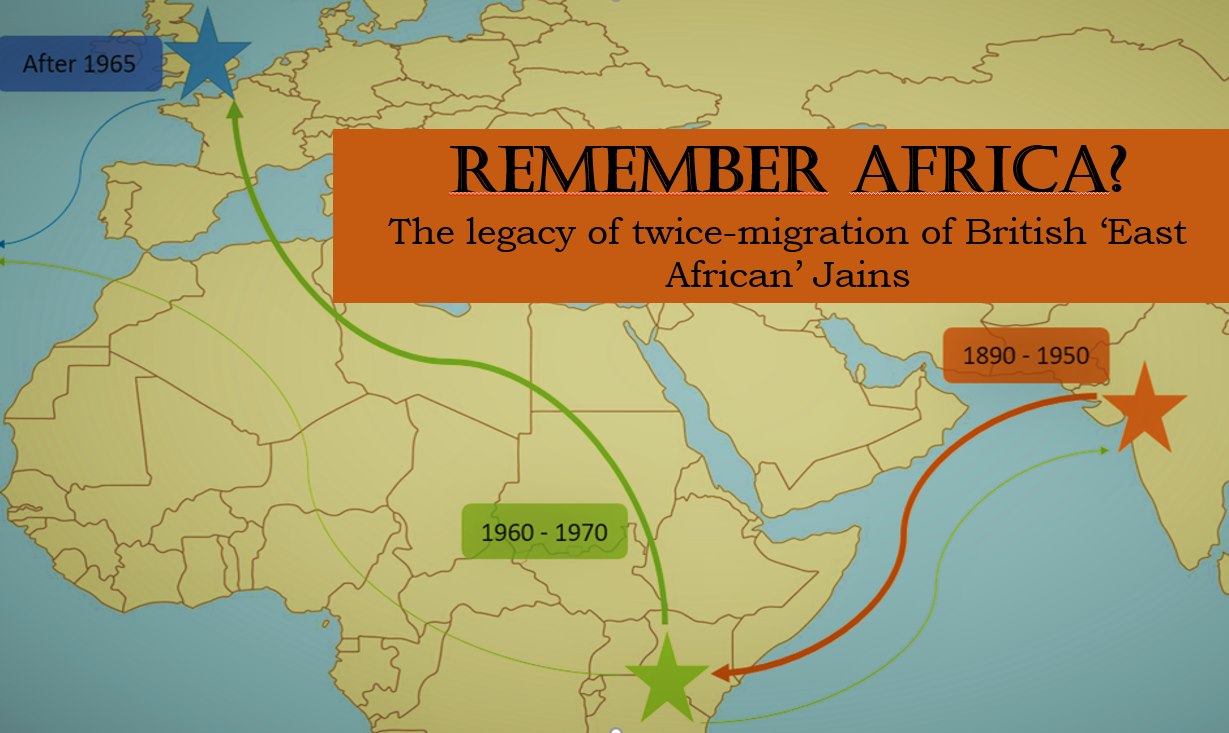

Featured Member shines a spotlight on the diverse research interests of, and the exciting projects undertaken by, those affiliated with the Cultural Memory Studies Initiative. In this fourteenth instalment of the series, we speak to Tine Vekemans, an assistant professor and postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Languages and Cultures at Ghent University. Dr Vekemans’s FWO-funded research project Remember Africa? The Effects of Twice-Migration on the Religious and Cultural Lives of British “East-African” Jains examines different types of contemporary memorial projects and narratives of individual Jains in the UK to understand the experience of “twice-migration” and its impact upon religious and cultural praxis. Some of the topics discussed in this conversation are the origins of Dr Vekemans’s interest in issues of memory, the importance of memories of everyday life, and the interconnections between the study of memory, religion, and migration.

Can you tell us a little about your research and how it has developed over the years?

My central research interest lies in migration and the way it affects the way individuals and communities experience, develop, and practice their culture and religion. This interest grew throughout my time studying Indian Languages and Cultures and Conflict and Development at Ghent University, and further developed during the eight years I subsequently spent as an interpreter, intercultural advisor, and social assistant in the migration sector. I consider myself privileged that so many people shared their life stories, memories, and migration histories with me at that time. Neither they nor I realized at the time just how foundational these interactions would turn out to be to my future academic work.

I rejoined my Alma Mater, Ghent University, over a decade ago, when I applied to do a PhD in the Department of Languages and Cultures. The South Asia Network Ghent Research Group became my primary hub, but I have been active in other research groups as well, such as the Centre for Global Studies, the Migration Working Group (now part of CESSMIR), and the Cultural Memory Studies Initiative (CMSI). Since 2013, I have used ethnographic methods combined with textual and media analysis to examine various aspects of 20th- and 21st-century Jainism (a small but influential South Asian religious tradition): the role of digital media in the practice and dissemination of Jainism changing modes of lay-mendicant interaction in contemporary Jainism, and histories and trajectories of development of different “overseas” Jain communities.

What first attracted you to studying Jainism, and how has memory come to play a central role in your research?

When I started thinking of applying as a doctoral candidate, I was sure I wanted to look into migration and religion, but unsure about what community or case I would prefer to study. However, the Department of Languages and Cultures has a long history of research into different aspects of Jainism, so that settled it. I have not regretted this choice: Jainism is a very rich and interesting tradition, with a vibrant transnational presence which developed in different phases. First the precolonial circular trade-migration morphed into more settled trade migration structured by the exigencies of Empire from the end of the 19th century. Subsequently, the postcolonial world opened up new avenues for student and business migration, while closing others.

It was when I started looking into the history of migration foundational to today’s Jain communities outside of South Asia that memory – and memory studies – became central to my work. Whereas the economic and political impact of the presence of South Asians in places like British East Africa has been the topic of some academic research, not much at all has been written about the cultural and religious lives. However, recently, the dwindling of the generations who lived in East Africa as adults has resulted in a surge of memory writing and memorial projects in the Jain community itself. And through these sources, as well as life-story interviews, I hope to access understudied aspects of the history of Jains in East Africa: how early settlers as well as later arrivals experienced and practiced their tradition, how aspects of day-to-day life such as food-related practices and social activities were adapted to new contexts, how religious education was arranged for the next generations, how the community organized in ways that differed – radically or subtly – from the modes of organization common in India. At the same time, the fact that so much writing, sharing, and remembering is taking place now (roughly since 2005) is in itself an interesting dynamic to examine. This surge comes at a moment when historical events foundational to some of the current diaspora communities are fading from living memory. Although this rush to remember is often clearly driven by a very personal wish to record family histories before they pass beyond salvaging, the cultivation of collective memory through memorial projects also indicates a conscious strategy to affirm aspects of identity and organization in younger generations.

In your work you try to bring out memories of the everyday life that preceded Jains’ migration first to East Africa and then to the UK. What are the challenges of dealing with such a fleeting subject?

The everyday tends to be underrepresented in academic as well as media sources. The business success of South Asians in East Africa and their in-between position between the local African population and the mostly British colonizers have been discussed at length. This lucrative arrangement turned precarious when anti-colonial nationalist movements and policies towards Africanization questioned the role and position of the South Asian minorities in the nascent independent societies and markets (e.g. the Zanzibar Revolution, the Mau Mau rebellion, and Idi Amin’s expulsion of Asians). These geo-political circumstances which caused a significant percentage of South Asians to migrate within and beyond Africa have also received the attention of scholars and reporters. However, the development of subtly adapted and contextualized cultural and religious practices of the “twice-migrant” communities I study can hardly be found in these big events and success stories. It needs to be traced by looking into everyday practices that evolved during and after the move from India to East Africa in the first half of the 20th century, and during and after the move to the UK in the 1960s and 1970s.

But even as I attempt to elicit narratives and reminiscences on everyday life, interview respondents often tell the “big story” first, and find it difficult to believe that I am interested to know what stories their mom told them, what songs they remember singing, what food was on the table, what books or figurines were in their home-shrine, etc.

In focusing on “twice-migration,” you address complex transcultural and transnational phenomena that are inevitably affected by postcolonial dynamics and processes of identity construction. What impacts do these dynamics and processes have on your case studies, and how do you navigate such a complex landscape?

I love the complexity of this landscape. Although I focus on a rather specific case, a community of “twice-migrant” Jains in the UK which now numbers only some 30,000 people, their experiences connect with so many aspects of global history: changes in mobility in the Western Indian Ocean world and beyond, the development of legislation pertaining to migration and citizenship, different perceptions of race and religion, shifts in subaltern and international solidarity,etc. This complexity can also help us get rid of some entrenched assumptions based on overly nation-focussed interpretations of history and dichotomies of West and East, local and global, us and them, then and now. Looking at the history of Jains moving from India to East Africa to the UK and beyond shows very clearly how colonial history and the rise and fall of Empire still structure the contemporary world. 19th- and early-20th-century colonial circumstances enabled the first leg of the twice-migration, and colonial legacies and sensibilities as well as postcolonial migration policy shaped the second.

Moreover, this case also exemplifies how complex and fluid attachment to “a nation” can be, and how mobility has changed in a much more complicated way than the linear move from local to global we often envisage.

Your work deals with individual memories and memorial projects that have profound importance within the Jain community. How do you think your work will benefit that community – if at all? And, more generally, what impact do you hope to have beyond the academic world?

As this research would not be possible without my respondents’ trust and readiness to share their often personal and at times traumatic experiences, I try to give back in small ways whenever there is an opportunity. I have on occasion consulted for memorial projects such as Threads That Tie Us, a documentary by Canadian film-maker Bindu Shah. I am also involved in The Jain Migration History Project, a community history project based in London. Some of the life-story interviews I do in collaboration with them are posted on YouTube. Not only are these interviews appreciated by the Jain community, but I recently learnt to my delight that one of these interviews is now also being used as teaching material in classes on Jainism and gender at UCLA in the US.

More generally, through writing, public speaking, and teaching I hope to show the intricate complexity of transnational, intercultural, and (post)colonial human experiences. A complexity that cannot be reduced to dualities such as good – bad, original – derivative, here – there, or even legal – illegal, and should, in my view, lead to a more nuanced and positive appraisal of diversity and migration in our own society.

Your research combines memory studies and religious studies. What does the latter field have to offer scholars of memory?

To me, these two inherently interdisciplinary fields do not feel very separate. Migration causes them to blend into each other: studying cultural and religious aspects of migration always necessitates exploring how individuals and communities engage with the past. As to what religious studies can offer memory scholars: I feel it is important to be aware of how religious (but also cultural or sectarian) affiliation can structure what and how people remember, especially when we view remembering not just as an individual activity, but also as a social, potentially community-affirming, project.

Are there any specific texts, concepts, or methods from memory studies that you have found particularly useful?

I must admit that I am still getting acquainted with the field of memory studies. In addition to work on migration and memory, the concepts of intergenerational memory (Mannheim), collective memory (Halbwachs), and prosthetic memory (Landsberg) have helped me make sense of the reason for and dynamics of the current surge in memorial activities and memory sharing in the community I study. Over the coming months, I hope to read more on the socio-psychological aspects of memories of the everyday vs. memories centring on big (disruptive) events. Recommendations are welcome.

Are there any recent or forthcoming conferences, exhibitions, or other events that you are particularly enthusiastic about?

I was fortunate to participate in my first Memory Studies Association conference in Newcastle in July. I greatly enjoyed this experience, and hope to attend regularly in future. Something to look forward to in the nearer future is Prof. Vandana Saxena’s stay in the Department of Languages and Cultures as a visiting researcher. Vandana works at Malaya Universiti in Kuala Lumpur, and will share my office for a month in October. As she has worked extensively on South and Southeast Asian postcolonial literature and memory, I look forward to learning a lot through interactions and collaborations with her.

Interview conducted via email by Guido Bartolini and Stef Craps.